Creating patient-centered connected health experiences is very personal.

It’s simultaneously important to many players beyond the patient. To create meaningful connected health experiences that produce measurable and repeatable outcomes, it takes a lot of data, individualized content and most of all an approach to the user experience that is inherently user-centric.

It starts with the patient and expands around them to include physicians, hospitals, provider networks, life sciences companies, the pharmaceutical and insurance industries, and academia and research. All of these players encompass the ever-growing and expanding healthcare ecosystem.

Every year the next revolution in healthcare takes off. It wasn’t that long ago that mapping the human genome was thought to be a Herculean task. Now, we are able to go from theory to production and distribution of a vaccine in less than one year. It’s not just the science of healthcare that is conquering uncharted territory. The individual experiences we each have engaging the healthcare industry are changing at a rate unfathomed just a few years ago.

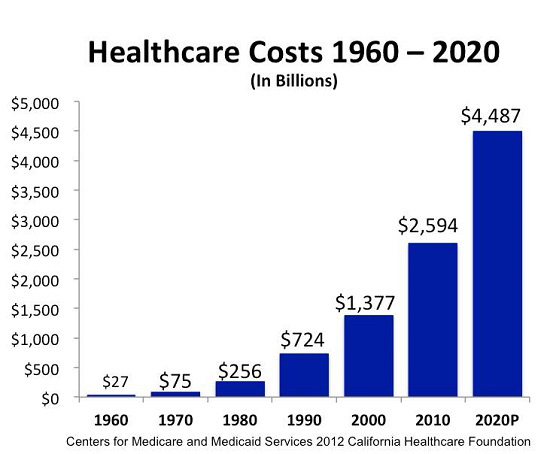

The healthcare industry is immense. Global healthcare spending is expected to reach the $10 Trillion USD level next year in 2022. In the US alone, there are almost 800,000 companies in the healthcare sector, ranging from individual practices to McKesson, the largest healthcare company with annual revenues in excess of $200 Billion USD.

There are doctors, clinics and hospitals, systems and networks. There are payors including insurance companies and government programs like Medicare and Medicaid, research institutions like universities, the CDC and the WHO, and private firms including pharma, medical devices, life sciences and biotech.

It is the relationship between each of these players and the patient (the healthcare consumer, customer and recipient), that defines the experience every individual undergoes each time they engage and interact with the healthcare ecosystem.

At the center of it all is the individual. For them the only thing that matters is the positive outcomes of their connected health experiences. And, at the core of all the relationships that intersect with the individual is the need to diligently and unceasingly protect their personal privacy. PHI and PII data must be safeguarded while, at the same time, anonymized data can be critical to diagnoses, research, clinical trials and statistical analysis.

With their privacy protected, the individual wants and expects to have a connected health experience that is personalized, individualized and contextually relevant to their unique situation. The ability to assemble, present and react to the right content for every patient requires the right combination of data and content, all managed via an optimized program built on a secure and scalable content platform, and presented dynamically through a personalized digital experience, regardless of time, location or device.

Delivering this unique experience is a combination of program, process and technology. For each stage in the user journey, including patients, providers and researchers, there needs to be a program established that defines what the set of experiences will entail. To make these programs work requires well-defined processes, including workflow and governance; established, enshrined, and to the greatest extent possible, automated. All of which lead to being able to design, build, test and deploy the right technology on the right platform that will serve all the parties involved and do so as efficiently and effectively as possible.

What does a good connected health experience look like that combines, program, process and technology, all integrated to produce the best patient outcomes? Let’s take a look at -

A Prime Example of Connected Health – MyMobility from Zimmer BioMet

One of the most innovative solutions in connected health is the MyMobility program from Zimmer Biomet. MyMobility guides patients through a personalized and contextualized connected patient experience. It delivers content experiences comprised of customized protocols from the patient’s medical team, including medicine, pre- and post-operative exercise regimes and telemedicine. It tracks, collects and monitors engagement, progress and adherence to the patient’s individual protocols along their entire healthcare journey.

The MyMobility program is built on a digital care management platform that uses iPhone and Apple Watch, powered by an integrated content platform utilizing RWS Tridion CMS and Aprimo DAM solutions as the core technologies. This platform allows the entire care team to establish the individual protocols in the areas of education, exercise, PROMs and calendaring, all utilizing the same underlying architecture and infrastructure.

The platform decouples all PHI data from the content and delivery systems, ensuring complete privacy for the patient while still maintaining data integrity, flow, management and efficient systems operations.

In addition to the immediate benefits to patients and their medical providers, MyMobilty is a valuable source of patient-reported outcome measures and PROMs, anonymized and privacy protected. MyMobility collects, organizes, manages and maintains data valuable for measuring outcomes during clinical trials, benefiting provider networks, life sciences, pharmaceutical and academic research organizations dedicated to finding more efficacious solutions.

MyMobility’s success lies in three distinct approaches to designing, developing, deploying and supporting the programs. First, it requires taking a customer-first approach to the user experience design. If it didn’t conform to the way people lived their daily lives, it would not be successful. Every connected health solution must begin with gaining a deep understanding of patient behavior, motivations and comfort with a new type of healthcare experience.

User-centered Design

One of the maxims of user experience design is known as Jakob’s law. It states that people prefer experiences that work the way they are accustomed to working. When people come to a website, they expect navigation choices to be at the top of or along the left side of the page. This isn’t the only way to design a web page, but it takes advantage of already existing mental muscle memory to improve engagement.

When applied to connected health, Jakob’s law is important to maximize the adoption of the experience and to minimize the need to “learn” how the experience works. This is equally true whether you are talking about the patient experience or the physician’s experience. Neither are technology experts and neither expect a steep learning curve. If it’s not intuitive and easy to use, they simply won’t use it. Their perception is that it is harder than their current method, no matter how manual or labor intensive, and therefore they will not change.

The first step in creating user-centered design is observing and analyzing how users behave, how they use current tools and listening to them when they tell you what’s most important from their perspectives. It is critical to understand the differences between different types of users, doctors, patients or researchers, for example, and even within a category of users there will be big differences based on many variables including age, education, experience and backgrounds.

Once the user experience design team has gained an understanding of who their audiences are and what motivates their behavior, they begin to look at all the features and functionalities associated with the connected health program. This entails working closely with the program owners and designers to understand what they want the experience to include. Are the communications one-way or interactive? Can you respond to your provider securely in real-time? Can you accomplish most of the tasks with a single click or swipe? These are the types of questions that the experience design team needs to review with the creators of the program.

From here, the user experience team can do their magic, creating an interaction model and a user flow that will define the end user experience for each type of user, with the ability for the experience to dynamically change for each individual.

The goal is simple, to make the design as easy to comprehend and use as possible. Think of Google’s user experience as a prime example. On the home page, there’s one blank box you simply type something into and it gives you results. The more complex the experience becomes the less adoption, and as a result the less of an impact it will have on patient outcomes.

Content Strategy

At the heart of a connected health experience is content. It may be a combination of text, images, video and more. The experience may include engaging with multiple types of content, all in different forms, consumed on different devices, in different times, at different locations and in completely different contexts.

Defining what content is needed, how it’s organized, managed and presented is all part of developing a content strategy that works for connected health experiences. Underneath the content is its metadata and taxonomy, the ways in which we can describe the content and make it findable through search or publication.

Compounding this complexity is the idea that each piece of content may be presented with other content, assembled in almost infinite combinations. This is what is meant by personalization. It isn’t necessarily creating new content for each person, but combining the various different content elements in a unique manner that fits each user.

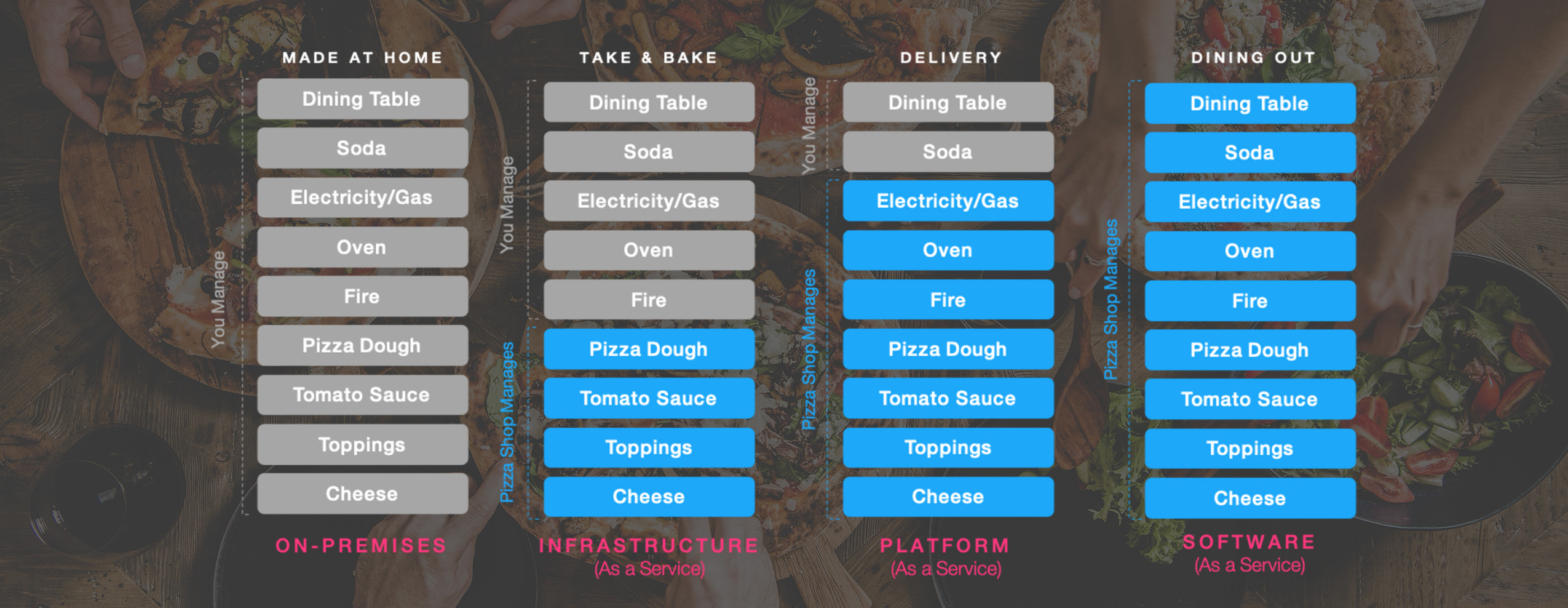

For example, everyone loves pizza, but the definition of pizza is different if you are in New York or Chicago or Naples. Within the concept of pizza, there are many choices as to size, crust, toppings and ways to cook it. Not to mention the context of pizza. Will you make it from scratch at home, buy a frozen pizza, get delivery or go out to a pizzeria? For lunch, dinner or the middle of the night? By yourself, with family, friends or the crowd that gathers outside? All of these variables exist when thinking about content and the way it needs to be assembled for each experience.

Another challenge for content in the connected health space is that healthcare is rife with jargon, acronyms and technical language in addition to brands versus generic. Almost all of it is a mystery to the patient, but critical to the provider.

This is where taxonomy and metadata are of paramount importance. Metadata describes the content, while taxonomy defines the language used to do so. From a customer-centricity point of view, it is critical that the taxonomy is modeled on the language being used and understood by each audience.

Luckily, there are automated tools that can unravel the underlying meaning using artificial intelligence applied to semantics. They can detect the incidence of specific language and identify the ontologies, which identify the concepts and their relationships to each other, and then inform the creation of universal taxonomies. The taxonomies inform and govern the metadata, and in turn make it possible to make the content searchable, whether it’s via search queries like Google search or by defining the navigation of a digital experience.

At the end of the day, making the content findable and presenting it in a consistent manner that all parties can share and understand is the primary determinate of successful digital experiences, which can result in the improved outcomes promised by connected health.

Data Strategy

The connected health experience is not lineal. It is multi-faceted, multi-directional and multi-channel. In order to decide what content should be delivered and which protocols should be followed, there is the need to compile, curate and manage data across all parties and organizations, in real-time and enabling both the immediate and longer-term analysis of the meaning and importance of the data.

The first question about healthcare data is not what is out there, but what is valuable. The World Economic Forum estimated that in 2020, the world created 44 zettabytes of data. That equals 40 time more bytes than stars in the universe. In healthcare alone, every single patient generates a minimum of 80 megabytes in EMR data every year. Experts predict that 7.5 zettabytes (1021 bytes) will require long term storage by 2025, a 581% increase from just 2019.

For connected health, data needs to be divided into two distinct and separate categories. First, there is PII, personally identifiable information, which connects to an individual. This includes name and address but also includes job, finances, taxes, social security and so much more. Next there is PHI, protected health information. This data includes past, present and future health conditions, treatments and services rendered to an individual.

In both cases, this is highly personal and protected data. For the purposes of this discussion of connected health experiences, it is assumed that all PII and PHI data will be sourced, processed and stored in a completely separate environment from the experiential data related to delivering a connected health experience. Access to elements of this data should only be made available as needed to personalize the experience, and should not be duplicated or exported out of its secure repository. With the emerging potential of distributed ledger technology including blockchain, the ability to protect and simultaneously limit the access to PII and PHI data is becoming greatly improved.

The second category of data is that related to the experience itself, exclusive of PII and PHI data. It is the data enabling, tracking, and measuring of the experience itself. It defines what content should be presented, in which context, and to whom. And it does so by understanding the relationships between different entities associated to the experience.

For example, there’s a relationship between doctor and patient, but there are also relationships between doctor and network as well as between patient and network. Some of these relationships are obvious; the doctor is in or out of the patient’s insurance network. Others are harder to see, as in the following example.

The university where the doctor got their degree developed new protocols now being tested through clinical trials involving subjects, one of which is the patient’s relative, and the reason the patient is searching for data about the clinical trials and their potential applicability in their case. The various parties sound disconnected but in the patient’s mind there is a direct connection, influencing their behavior and the relationship they have with their doctor.

Graph databases are built to aggregate data from disparate sources and to discover the patterns and relationships that flow from each situation. This is an example of how to convert raw data into meaningful and actionable insights that can be used to optimize the connected health experience.

Graph databases are often used to store knowledge graph data. A knowledge graph can best be defined as essentially a model of a knowledge domain created by a combination of subject matter experts, aided by intelligent machine learning algorithms. It provides a structure and common interface for all your data and enables the creation of smart multilateral relations throughout your databases.

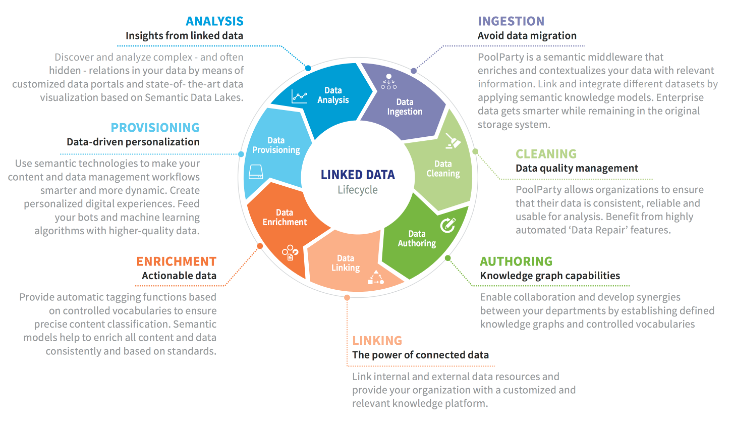

In the case of connected health, it is the creation, management and analysis of the knowledge graph data that will determine the success of the entire experience. The lifecycle of the data is comprised of specific stages. They include –

Summary

Connected health experiences require the disciplines related to content, data and experience design to work in tandem to produce experiences that connect all the players along the entire connected health journey. They need to be personalized and contextualized for each user, and to always protect the privacy of every individual.

Successful connected health experiences are the outcome of organizing at all three levels: people, program and platform. They leverage the best technology, the right expert resources and a commitment from all parties to contribute and participate in the entire process. That commitment spans all the way from vision and strategy through to design, development and, most importantly, continuously testing, measurement and optimization.

In the end, if the connected health experience is not centered on the patient and dedicated to improving their health outcomes, it will not be worth the investment.